Who Invented String Art — and How It Became What We Know Today

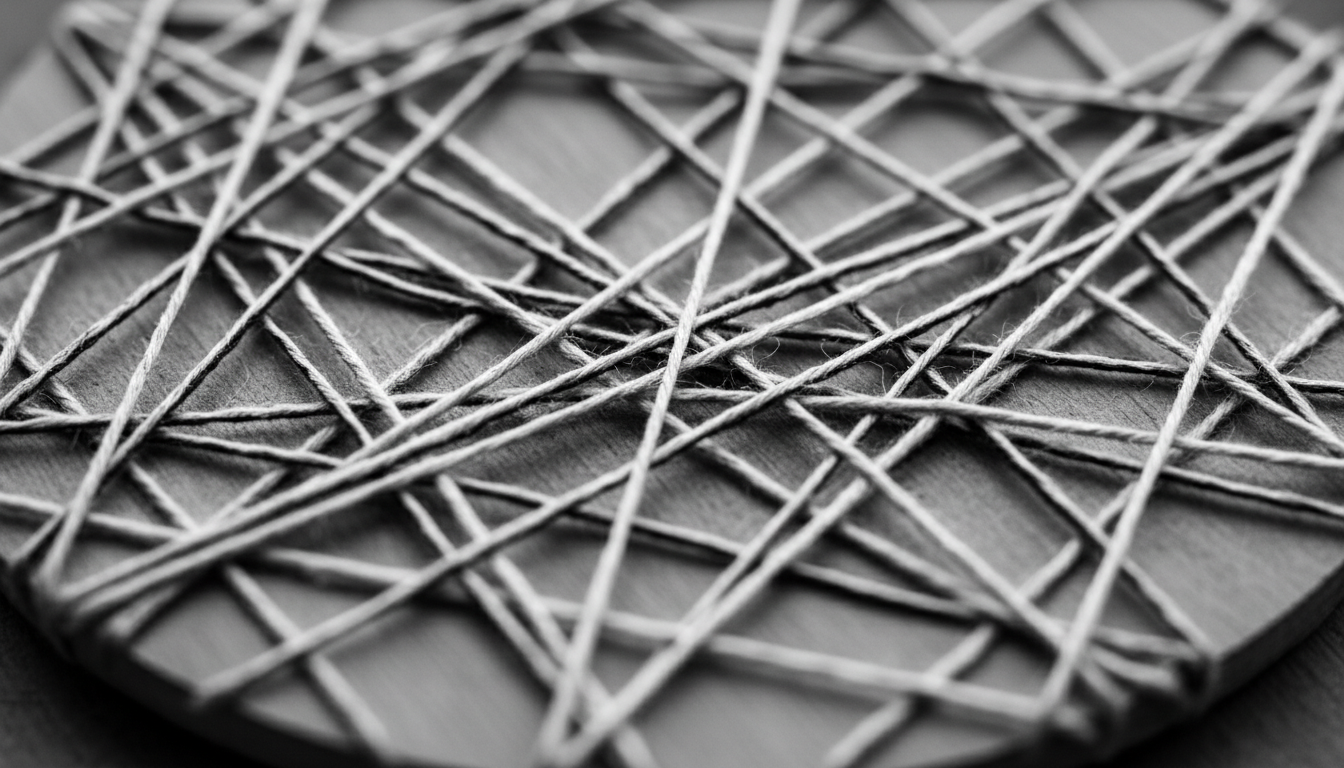

String art began as a mathematical teaching method called “curve stitching” and evolved into a modern art form where straight lines create the illusion of curves.

String art did not begin as decoration.

It began as a teaching tool.

The Unexpected Inventor

In the late 19th century, Mary Everest Boole, an English educator and mathematician, was searching for a better way to teach abstract mathematical ideas to children. Instead of formulas on a blackboard, she introduced something radically simple: straight lines arranged to suggest curves.

She called these exercises “curve stitching.”

The idea was intuitive. By connecting evenly spaced points with straight threads, students could see how curves emerge from order. No calculus. No advanced geometry. Just hands-on discovery.

At the time, it was not art.

It was visual thinking.

From Classroom Tool to Creative Medium

For decades, curve stitching remained largely educational—used quietly in classrooms to explain geometry, envelopes of lines, and spatial reasoning.

Then something unexpected happened.

In the late 1960s, string art escaped the classroom.

DIY culture was booming. Craft kits, instruction books, and hobby magazines began presenting string art as decorative wall pieces. Nails, boards, and colored thread turned mathematics into home décor.

What had once explained math now looked modern.

Bold geometric shapes, circles, and abstract patterns became popular. String art aligned perfectly with the era’s fascination with structure, systems, and repetition.

Why It Stuck

String art survived because it sits in a rare space:

- Logical, but not cold

- Structured, but expressive

- Mathematical, yet accessible

Anyone could make it.

Few fully understood why it worked.

That mystery became part of its appeal.

From Patterns to Portraits

In recent decades, string art evolved again.

Artists began applying the same principles—straight lines, density, repetition—to far more complex subjects. Faces. Animals. Emotional forms.

Portrait string art pushed the medium beyond decoration. Thousands of straight threads now suggest light, shadow, and expression. The mathematics remained the same, but the emotional impact deepened.

The original educational idea scaled up—quietly, elegantly.

A Legacy of Making the Invisible Visible

Mary Everest Boole’s goal was never to invent an art form. She wanted children to understand ideas that felt unreachable.

That legacy remains.

Modern string art still does what it always did:

- It makes abstract structure visible

- It turns rules into beauty

- It invites curiosity instead of explanation

What began as a classroom experiment became a global visual language.

And every string art piece—no matter how modern—still carries that original idea:

complexity doesn’t have to be complicated.

That is the true invention behind string art.

Share this article Share to

Written by

Join the conversation

String Art DIY Kits Compared: Model Circle M vs. Model Ring M

How Long Does It Really Take to Make String Art? (And Why That’s the Point)

Try Before You Start: Why Previewing Your String Art Changes Everything